”It’s all I can think about lately, you know? First contact. Not the one discussed in books, theirs or ours—I mean the very first. You’d be surprised how stunted most people are when I ask them to imagine. Is it such an outlandish proposition? Don’t you wonder about it, too? I do. I can see it more and more clearly these days. I call him ‘Brin’.

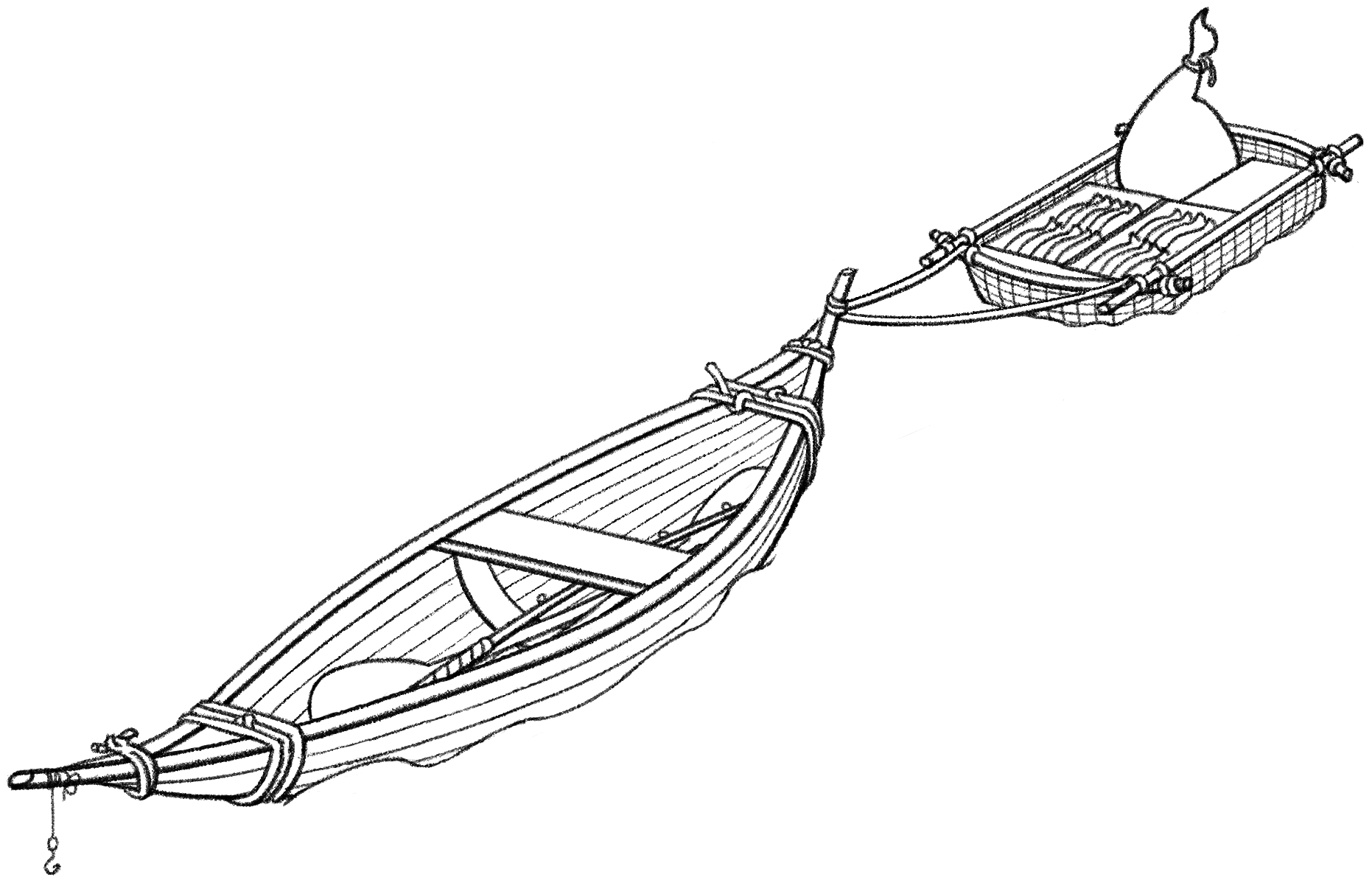

”Imagine Brin standing on our shore, palm trees holding off the rain as he’s waiting for his fellow fishermen to fasten their boats. He doesn’t know what’s waiting behind the bushes. He doesn’t know if there’s something waiting. So while he waits, Brin starts thinking of possibilities. You know how the Gralinn mind works. Stories from his childhood come back to him, of the monsters of Spor, Allayn assassins, let alone the Southrons. The leaves at the edge of the jungle aren’t moved by wind anymore, not in his mind. They’re hiding something, something that’s looking at him, watching him.

“So, while the others keep hugging and clanking bottles together, Brin draws his spear. The beach disappears, so does the ocean, until there’s only the jungle and him. And then, he spots the boy.” Elehi paused. ”It’s him that I struggle to imagine.”

The drumming of rain filled the room as he looked up. Across the table, past the bowls and carafes and delicious smells, Faroe had his eyes set on the roof, pondering. Elehi sighed. No man he had met inside Tahor or beyond would ever understand him the way the doctor did. He felt regret for having put off the visit for so long; the raids, the attacks, Koeiji itself had demanded his attention, sure, but they just made it more important for him to come here. He needed this. He needed a friend.

”Have you considered giving him a name?” Faroe asked.

”… I have not,” Elehi said. ”He’s Tahori, that’s all I know.”

”How about Jey?”

”That philanderer with the crookflute?” Elehi chuckled. Roaming the campus-side taverns of Yafa with Faroe, that hothead had been a regular sight trying to get into women’s sarifs. ”Sure, I don’t see why not. So, of course, Brin locks eyes with Jey the instant he spots him. The boy’s got eyes as green as the plains. His skin looks different than any Brin has ever seen. But what he doesn’t see is that the boy is distraught as well. After all, there’s a host of strange pale men on his beach wearing clothes of trimmed fur, some with hair brighter than the sun.”

”He’s seeing ghosts,” Faroe added.

”Exactly. There they stand, Brin and the boy—Jey, I mean, seeing only each other, both frozen in place. And… to be honest, I also haven’t made up my mind how the other fishermen act. Sometimes, they ignore Brin and his terrified eyes staring at the bushes; other times, they recognize Jey themselves. Perhaps one of them even walks up to him.”

”I’m sure we can find an ending for this… encounter.”

”Oh no,” Elehi said, raising his palms. ”I know the ending.”

The smile Faroe gave him was a weak one. Between the wafts of steam rising from the food, Elehi suddenly recognized that his friend was tired. Of course he was. Who knew what ungodly hours he kept these days. His home clinic’s business hours were always up for discussion when an emergency came knocking. On top of that, being called upon during the night to host him—the roasted pheasant alone must have taken hours to prepare, only to now sit amidst the bowls bristling with maize and rice, and listen to him meander. Elehi lowered his eyes. ”I’m sorry,” he said. ”I shouldn’t bore you with this. Let’s eat, shall we? I’m famished.”

”I won’t have it,” Faroe said. ”You can’t tease people like that.”

Elehi felt his spirits rise. ”I know the ending because it is inevitable,” he continued. ”You see, Brin, he is not looking at a boy, but a gatekeeper. All the monsters, assassins, cannibals he conjured in his mind aren’t gone; they’re only a bit deeper in the jungle now, waiting for Jey to run back and unleash them at his whim. This terrifies Brin; so much so that he breaks free from his spell, and flings the spear.”

”And it kills the boy.”

Elehi smiled. ”No. It grazes him, wounds him perhaps. But he escapes, instantly, effortlessly. He knows the terrain. Brin’s compatriots immediately start scolding him, no wonder—they aren’t blind to the danger he put them in. But they’re still calm, which freaks out Brin all the more. He lashes out until they detain him. Face pressed into the sand, he screams, fights back until they let him break free. He unfastens one of the boats and begins lunging the paddle at the sea desperate to leave the shore behind. His arms start burning, and he groans. Suddenly, he hears the voices of the other fishermen on the beach behind him. They go from talking to shouting to screaming before silencing, one by one. But Brin doesn’t look back. He can’t. All he can do is paddle, and hope his arms don’t give out.”

”And they don’t?”

”… Not in my mind.” Elehi took a deep breath and noticed once more how hungry he was. But Faroe had not touched his side of pheasant yet. The host’s honor was the least Elehi could give him, even if it stirred up his stomach.

”So he will carry that story back to Grale with him. Tell the younger fishermen what awaits on the shores of Tahor.”

”On any shore that isn’t theirs. And therein lies the cycle.”

”Hm.” Faroe shrugged a tired shrug. ”It’s a neat story.”

”It’s more than that. I can’t… can’t get it out of my head. Every fresh soldier they send here has that same look on his face, like we’re all one spear throw away from turning into wild animals. And how can I blame them? They’re nursed at the teat with dozens, hundreds of stories like Brin’s. And on top of that…” He paused, choosing his words carefully. ”Some stories are true. All the skirmishes, the attacks… Our kin doesn’t seem able to see that this cycle cannot be broken only from one side. The Gralinn want to trust us, Faroe—all we have to give them is something to trust in!”

Something changed in Faroe’s demeanor. He leaned forward crossing his fingers, intertwining them above the steaming food on his plate. ”But the spear has been thrown.”

”And those that threw it have been brought to justice.”

”Debatable. You know what the papers call it, don’t you?”

Elehi groaned. ”I know what the lowest scum of journalism calls it. ‘Lodge justice’. Didn’t peg you for a reader.”

”They do have a point. A home in the countryside can hardly be called a prison, especially when crimes against the Empire earn us and ours capital punishment.”

Elehi’s hand bumped against his own plate filled with a mountain of steamed egg cabbage, rice, and a pheasant leg. An avalanche of tiny cabbage heads tumbled down the side of the mountain before crashing onto the tablecloth. Elehi didn’t react right away, but instead just watched as the oily sauce seeped into the beige fabric. He was dumbfounded. ‘Crimes against the Empire’, ‘capital punishment’—Faroe couldn’t be this outright. He knew his friend to choose his words more carefully than that. But his eyes rested on him still, ignoring the mess. Elehi cleared his throat. ”I’m sorry,” he said, ”I didn’t mean for this to turn political. To tell you the truth, that’s the last thing I want to discuss over dinner.”

”I feel the same.” Faroe pushed his plate just a bit further onto the table. ”Which is why I’m not eating yet.”

”Please, Faroe, tonight of all nights… Don’t do this.” A heavy sigh left Elehi’s chest. ”I have enough naysayers around me the rest of the day. I don’t need my friend judging my every move, too!”

Before he even realized he had raised his voice, the door already swung open. About three dozen picture frames rattled on the walls as Odessyn stepped in with his gun drawn. ”Prefect Rai, you—”

”Get out,” Elehi snarled at him. ”I make noise when I want to, understand?”

”Yes, prefect,” the pale soldier said. ”Excuse my imperruption.”

Odessyn’s face, him even being here was a pain to Elehi. It wasn’t enough to have a man looking over his shoulder at work, no; the riots and protests had forced him to keep a permanent detail. ”Go ahead and join Kav outside,” he said.

Odessyn halted for a moment. ”You are positive, prefect?”

”What, afraid to get a little wet? OUT, NOW!” Odessyn closed the door behind him, hardly more carefully that he had ripped it open. As the picture frames settled, Elehi pursed his lips. ”You were about to bring up the trial, I believe.”

”It was hardly a trial.”

”Yes it was. Public order was threatened, I was within my rights to sentence them. Trust me, in one month, you’ll be thankful.” He was sick of having to defend what was already set in stone. ”They have to understand that there are consequences.”

”Perhaps, but not an execution. They merely damaged a building. No person came to harm through their actions.”

”They defaced the municipality!” Elehi yelled out. This time, the door stayed closed. ”That’s the Empire’s building, for crying out loud! Not to speak of what the rest of the mob did to the inner city. They’re criminals, the entire bunch, and words are lost on them.”

”They’re children, Lei.”

Elehi felt a sting. Not since Joji’s death had anyone called him by that name. Faroe knew how it made him feel; he must have felt the same, bringing up her memory. But as anger stirred inside him, Elehi also realized that the argument was lost. Had his sister gotten one look at the frightened little creatures in their jail cells, she would have gnawed his ear off, cried and pleaded until he caved in and released them. Faroe knew that as well as he did. It was one reason why he had wedded her.

”Did you have to say that?” Elehi asked.

”You can’t continue like this. An example won’t restore the peace, not the way you want. More and more people coming through my clinic are talking about the TLA without even trying to distance themselves.”

”So? Someone’s always talking. Curses, some mention the Liberation Army to seem dangerous when they meet girls!”

”Stop acting like a fool,” Faroe said. ”Whoever comes to my clinic knows who I am. Who I am close with. They’re getting reckless.”

”I CAN’T, FAROE!” Elehi found himself screaming. When he lowered his voice, it was jumpy, and his hands kept shivering. ”I can’t, alright? If I call off the execution now, not only will the entire city judge me a coward, the Empire will also start looking for my replacement. There’s talk of one of theirs being groomed for the position. Can you see that calming down the situation? A pale prefect running Koeiji? A fucking sweat?” He banged his hand on the table, toppling over another cabbage. ”I am all that stands between us and them. I cannot argue with the ghost of Joji, and fuck you for bringing her into this. But the decision has been made, bad or not, and sticking it out is my only chance at keeping what little autonomy we have left.” He exhaled, letting his words sink in. ”You’re right, my friend. But no.”

Rapid muffled drums filled the room once more as the storm built up further. Faroe’s eyes finally left Elehi behind and veered off, staring into space. Deep crevices appeared on his forehead. Elehis words had gotten through. Relieved, he leaned back in his seat and looked at the window. Every now and then, distant lightning flashed brightly through the stream of water running down the panes. But the only rumble came from his stomach.

”You’re…” Faroe faltered. ”You’re honest with me. I cannot ask more of you.”

Elehi smiled and toyed with the small cabbage heads. ”You could ask for a new cloth.”

Faroe returned his smile with an even more tired one. ”You’ve spilled on this one many times before. It’s a small price for your time.”

As soon as the doctor’s hand picked up spoon and knife, Elehi gave into his urges and dug into the mountain of food before him. Hungry as he was, even the cantina of the municipality would have satisfied him, but Faroe’s cuisine was worlds beyond. Spices from all the regions of Tahor and beyond flooded his mouth. The cabbage heads were so soft that a twinge of his spoon could squish them. Soon, he had to stop to catch his breath, and painfully force the half-chewed clumps down his throat with gulps of dark red spirit..

It wasn’t until his late twenties that Elehi had realized the reason for his friend’s culinary skill: his mother had been around to teach him. At the lowest points in his life, Elehi did feel envy about that, and other privileges that his own parents’ disappearance had robbed him of. Recent years however had gifted him an eye for the burden that a happy childhood could put on a man. True, Faroe knew how it was to be loved, to be protected by parents that wanted him. But he also knew how it felt to lose them. What it did to people.

”Wherf fe lil one?” Elehi mumbled, spitting out kernels. He swallowed. ”Is she asleep?”

”She’s at a friend’s house,” Faroe said. There was a sense of pride about his voice.

”O-ho! Well, if that isn’t a first. I’d be insulted, still, but since I barely announced my visit…”

”She would have cancelled her sleepover like that.” Faroe snapped his fingers. ”She misses you.”

”Being missed is easy. Taking care of her, on your own… I don’t know how you do it.”

”I’m not alone. She helps out almost every day in the clinic. My patients seem to enjoy talking to her during operations, it distracts them.”

”Still with the questions?”

”I fear she won’t ever run out of those.”

Elehi took a moment to lick his teeth clean of the cabbage pieces and took stock of the crater on his plate. Next to it, the pheasant leg had not yet been touched. He dropped his knife and spoon without hesitation and lifted the greasy meat up to his lips. ”Well, perhaps she won’t believe all the stories then,” he said before sinking his teeth in.

Faroe chuckled, raised his brow, and cleaned a kernel off his lip with a napkin. ”Like Jey and Brin?”

”Uh-uh,” Elehi mumbled. It took him a while to process the stringy, yet tender flesh. ”Brin and Jey, mind you.”

”Of course. But regardless of the title, I’m sure she would have plenty notes.”

”Like?”

”The ending is… unfortunate. Brin doesn’t have to hear any shouting from the beach. The other fishermen don’t need to die at all. All he needs to remain fearful and tell stories is the possibility of danger, and his own cowardice to haunt him until the end of his days.”

”It would be neater, I give you that.” Elehi swallowed. A blissful post-meal fatigue settled in him, and he had to take a break. ”But tell me this: Suppose a hundred, maybe two-hundred years ago, a group of ‘ghosts’ did land on these shores. If one of them attacked a young boy from a fishing village, what do you think the men of that village would do?”

”It depends.”

”All it depends on is whether the ghosts would untie their boats fast enough to not be slaughtered. You embarrass yourself by idealizing the olden times, my friend.”

”There’s just as much embarrassment in belittling our ancestors.” Faroe cleanly inserted a slither of pheasant into his mouth. ”But even assuming you’re right, it’s still a story. Who cares about the actual time period, or the actual people? If all of it’s based on past facts, you’ll carry those facts into the future instead of leaving room for them to change. And therein—” He drew out the word while smirking at Elehi. ”—lies the cycle.”

”Oh, what an insufferable ass you are,” Elehi bellowed. ”I’d like to propose once again that you go fuck yourself.”

”What else do you think I’d be doing at this hour if it weren’t for your company?”

Both men broke out laughing, loudly, their booming voices drowning out the rain for a while. From how his body was shaking, Elehi would have expected the walls to shake as well, but looking up, he found the picture frames unmoving. As the spasms of his chest went down, he started looking at the black-and-white sceneries contained within the frames. Most of them he knew intimately. Half a dozen were hung in his office.

But one drew his view more than any other: a small, yellowed photograph hanging next to the door showing him, Faroe, and Joji as children in the woods of western Koeiji. Elehi and his sister were still climbing down the rocks that surrounded the small stream visible in the corner of the picture while Faroe spurred them on. Faroe’s father had captured the moment, his main challenge being keeping the wife from entering the frame to safeguard the little climbers. He likely would have forgotten that detail if the picture hadn’t accompanied him through life to remind him.

”That’s my favorite one,” Faroe said.

A burp was uttered. Elehi realized it was his, but even though his stomach was filled to the brim, he immediately went in for seconds. ”Better days. Not all-around, sure; but there was a blessing in how things were.”

”Smaller. None of us even had radios.”

”Remember when Joji got her first one? She’d worn out the batteries within a week. I still wonder if she got any sleep at all…”

”She didn’t.”

Elehi shortly choked on the last of the cabbages. ”What’s that supposed to mean? You weren’t dating yet at that point.”

”Not to your knowledge, no.”

”I’ll be… You kept that secret all this time?” Elehi was baffled. Such an effort from someone of Faroe’s neediness to discuss things—it was a compliment more than anything. ”I’d have you drawn and quartered if the food wasn’t so good.”

”Wasn’t my decision. Joji always was afraid about you finding out small things. Like when she smoked your cigarettes.”

”But that was for good reason. Boy, was I mad.” He lowered the near-clean bone from his mouth and looked right, at the old picture. ”I was mad at her quite often.”

At the thought, arguments settled and unsettled came before his mind’s eye, children’s quarrels, teenage screamfests, and the odd big argument they had as adults. It wasn’t long until the final one played out in his head.

”Oh Elehi, you’re not still pained by this, are you? She’d forgiven you already.”

”I didn’t get to show her—” His voice escaped his control. He suddenly felt tired, tired and full, unable to ban the stupid, destructive words he’d said to Joji from ringing in his ears for the thousandth time. Tears welled in his eyes. ”I was going to apologize,” he said. ”Not like before, not by talking my way out of it… Really apologize! Like she wanted me to. Now she will never—” Silencing himself was all he could do not to cry.

”She knew you could change for her,” Faroe said calmly. ”She’d seen it dozens of times. Like when she smoked your cigarettes to stop you from smoking. You were mad. But you stopped.”

Elehi heaved a deep sigh. The tears kept coming for a while, but finally stopped. Wiping his wet, stubbly cheeks, he felt the toll that work, dinner, and this conversation had taken on him. Faroe was the only one who he could bear seeing him like this. Slowly, he forced his eyes to make contact with his friend’s. ”If any man deserved to be with her, it was you,” he said. ”You truly were made for each other.”

The weight of his words only dawned on him after they had left his mouth. Despite his pure intention, it wasn’t the thing to say after her death. A flicker went through his friend’s eyes. He was close to tears as well.

”What a cruel thing to say,” Elehi said. ”Please forgive me.”

”There’s nothing to forgive. You’re—”

”Yes, there is.” He slammed his palm down on the table. ”Every time I come here, I disturb your sleep, eat your food, and spill my grievances. The least I could do is not make you cry by yammering about my sister.” It pained him to say the words, but they were true. ”My loss is nothing compared to yours.”

Faroe suddenly burrowed his face in his hands, and sobbed. Elehi failed to react. Staring at his friend, he wanted nothing as much as to console him, but knew that words couldn’t. His body felt like it had accepted the chair as his bed for this night. He forced himself to sit upright, and grabbed the table with both hands determined to stand up and at least give the doctor a hug.

”I’m sorry,” Faroe said quietly from behind his hands.

Elehi halted his ascent. ”None of it was your fault. Or anyone’s.” He watched Faroe emerge from his palms, tears smeared all over his face. Elehi smiled. ”You hear me?”

”No, friend,” Faroe said. A bitterness rang in his voice as he looked up. ”I’m sorry.”

For a while, Elehi just stared at him, perplexed. Over the years, Faroe had delivered him the most sincere of apologies, all of whom he had accepted. Did Joji’s fate still fill him with that much guilt? There was something else in the doctor’s eyes that unsettled him, though, something he hadn’t seen in a long time, not in him. But he did get that look from other people. It was all he got from them lately.

”Faroe,” Elehi said with shallow breaths. ”You’re worrying me.”

Instead of responding, the doctor pushed his plate away from him, slamming it against one of the bowls. Elehi looked at the contents. Faroe had barely touched the food, much less the full glass of spirit next to it still vibrating from the impact.

”You… you’ve barely eaten.” His voice betrayed the calm demeanor he put on. ”How come?”

”Answer me this,” Faroe said. ”Can you talk about the things we have talked about tonight with anyone but me?”

”… No, of course not! Why would you—”

Faroe heaved himself up from the chair and walked around the table. ”Could anyone beside me say the things I have said tonight to you?”

”You know the answer.”

Elehi stared in shock as Faroe locked the door. ”Then you know what position you have put me in.”

Elehi tried to get up, but learned in that instant the true extent of his fatigue. Even lifting his hand was an excruciating procedure. Palm facing inward, he contracted his fingers as far as he could. They didn’t even come close to a fist. ”Your… your position is my friend,” he stammered.

”That I am, and always will be.” Faroe walked from the door to one of the armchairs in the corner and leaned on it carefully. ”But there are other things I am to other people. I’m a citizen of Koeiji, of Tahor. I’m a doctor. And—””

”What have you done, Faroe?” Elehi had ceased to mask his fear. He was pleading. ”Tell me this isn’t what I… Tell me that you’re not trying to kill me. Not you, too, please!”

”The time for trying has passed,” Faroe said. ”It is done.”

Elehi pressed his hands against the edge of the table and leaned forward. A surge went through his body as he mustered up what remained of his strength. Joints aching, limbs trembling from the stress, he slowly rose to his feet. The chair toppled over when he pushed through his knees. Elehi turned toward Faroe, and as his periphery began to blur, stepped forward with his hand still clutching the table.

The truth, for all he had feared it, gave him a strange clarity. If the doctor said it was done, it was; he knew what measures were required to take a man’s life. Only a fool would expect him to carry a saving antidote. Those rarely even existed, Elehi knew, and knew only because Faroe had often told him so. As his vision deteriorated further, he pushed forward along the table not driven by hope, or revenge. All that kept him going was the desire to know one thing.

”Why?” Elehi asked meekly. He instantly after stumbled in his step, and came falling down on the edge of the table with a crash. Bowls and carafes spilled, and soon, his weak body sunk to the floor.

Faroe’s voice sounded from up above, hardly rising above the incessant drumming. ”For three years, I have watched you plunge this city into fear, mistrust, and violence. You reason well, give the people justifications for arresting husbands and wives, crushing protesters’ skulls, sentencing children. It is a reaction, you say. One that the Empire binds you to. You call yourself their puppet.” He stopped. Rolling on the ground, his body numb and beaten, Elehi heard his friend take a few shallow breaths. ”A lie, and you know it is.”

”You could have—”

”I am not finished. A puppet can’t cut its own strings. At any point during your tenure, you could have resigned. But you didn’t. Because even I could never shake that conviction of yours that all our people need is power. When our people see you, Elehi, they don’t see Tahor’s power. They see its corruption.” He sighed deeply, as if to sign that he was finished.

”You could have said… so.” Elehi came to rest on his back, fighting to even lift his elbow off the carpet. A diminishing stream of sauce from one of the toppled flasks splattered down from the table, landing near his head. His mouth was filling with saliva. He spat.

”You pushed away all those who disagreed with you. Now you wish to kill children. What reason do I have to believe you won’t come after me? After her?”

Elehi’s breath became hectic. He wanted to debate Faroe, wanted to prove him wrong, which he was. But it was clear that his words were limited. Already, his mouth was watering again, his lips getting number. A clacking noise sounded. Faroe’s steps walked back to him. Then, his body sat down on the carpet with a thump.

Elehi felt his head being raised, and shortly after being put down on Faroe’s lap. Looking up at his friend’s face, he lost all will to argue. Never had he seen such sorrow there. How has it come to this, he wanted to shout. But all that came out was gurgling.

And then he saw it. Above his head, Faroe’s shaking hand held up the yellowed picture of them hiking, climbing by the stream. Little Faroe shouting at him and Joji. Faroe’s mother just outside the frame, ready to jump in, should somebody slip on the wet rock. The tension left Elehi’s body gradually, smoothly, without any further panic. His mind wasn’t occupied by death anymore, nor stories. That moment was all there was, the promise of all that could have been, and wasn’t.

Faroe said something, but it didn’t reach Elehi. The doctor’s muffled voice had faded out with the drumming long ago. Even Elehi’s eyelids were now closing in, swallowing the picture from above and below. Yet it stayed with him as he sunk deeper, down to where no voice could reach him. Down to where there was no pain, no struggle.

Joji would be there, waiting.